Image: Mist Shower Hack Kit. Jonas Görgen.

The daily shower would be hard to sustain in a world without fossil fuels. The mist shower, a satisfying but forgotten technology which uses very little water and energy, could be a solution. Designer Jonas Görgen developed a do-it-yourself kit to convert almost any shower into a mist shower and sent me one to try out.

The Carbon Footprint of the Daily Shower

The shower doesn’t get much attention in the context of climate change. However, like airplanes, cars, and heating systems, it has become a very wasteful and carbon-intensive way to provide for a basic need: washing the body. Each day, many of us pour roughly 70 litres of hot water over our bodies in order to be “clean”.

This practice requires two scarce resources: water and energy. More attention is given to the showers’ high water consumption, but energy use is just as problematic. Hot water production accounts for the second most significant use of energy in many homes (after heating), and much of it is used for showering. Water treatment and distribution also use lots of energy.

In contrast to the energy used for space heating, which has decreased during the last decades, the energy used for hot water in households has been steadily growing. One of the reasons is that people are showering longer and more frequently, and using increasingly powerful shower heads. For example, in the Netherlands from 1992 to 2016, shower frequency increased from 0.69 to 0.72 showers per day, shower duration increased from 8.2 to 8.9 minutes, and the average water flow increased from 7.5 to 8.6 litres per minute.

In many industrial societies it’s now common to shower at least once per day

Altogether, the average Dutch person used 50.2 liter of water per day for showering in 2016, compared to “only” 39.5 litres of water per day in 1992. This is a conservative calculation: these data do not include the showers taken outside the home, for example in the gym. Research shows that in many industrial societies, and especially among younger people, it is now common to shower at least once per day.

The original man-made shower. Pouring a bucket of water over one’s (or another person’s) body. Image: Daniel Julie (CC-BY-2.0).

Taking the Dutch as an example, let’s look at the energy use and carbon emissions of a daily hot shower. Heating 76.5 litres of water (8.9 minutes x 8.6 litres per minute) from 18 to 38 degrees Celsius requires 2.1 kilowatt-hours (kWh) of energy. Depending on the energy source (gas, electricity), the carbon intensity of the power grid (US/EU), or the efficiency of the gas boiler (new/old), the resulting CO2-emissions of an average shower amount to 0.462 – 0.921 kg. If we compare this to the carbon emissions of a relatively fuel efficient car (130 gCO2/km), the emissions of a typical shower equal 3.5 – 7 km of driving, and this result ignores the energy cost demanded by water treatment and distribution.

The emissions of a typical shower equal 3.5 – 7 km of driving

In principle, the energy for a shower could be generated by renewable energy sources. However, if eight billion people were to shower daily, total energy use per year would be 6,132 terawatt-hours (TWh). This is eight times the energy produced by wind turbines worldwide in 2017 (745 TWh). All (current) wind turbines in the world could provide only 1 billion people with a “sustainable” daily shower. Furthermore, the use of renewable energy sources doesn’t lower the water use of the daily shower. To be clear, renewable energy is part of the solution – solar boilers, biomass, heat generating windmills – but we also need to look at the demand side of washing in a post-carbon world.

More Powerful Showers

Since the early 1990s, low flow shower heads have provided a more water and energy efficient way of showering. These shower heads use between four and nine litres of water per minute, roughly half the flow rate of a normal shower (ten to fifteen litres per minute). Almost half of all Dutch households had a low flow shower head installed in 2016, but as we have seen, the flow rate of the average shower since the 1990s has been increasing, not decreasing.

A rain shower. Image: <a href="http://soak.com" rel="nofollow">soak.com</a>.

That’s because other Dutch people have upgraded to rain showers, which have a water flow of about 25 litres per minute – double that of a normal shower head, and three times more than what a low flow shower head uses. A 8.9 minute rain shower requires 222 litres of water and 6.3 kilowatt-hour of energy to heat it. The carbon footprint corresponds to 14.3 – 21.3 km of driving.

Life Before Showers

It may shock some younger readers, but only fifty years ago most people in industrial societies didn’t shower at all. Wall-mounted shower units, installed over the bathtub, became widespread only in the 1970s, and dedicated shower cubicles became a regular fixture in new homes only since the 1980s and 1990s. Before the arrival of the shower, people took one (or a few) bath(s) per week, and in between they washed themselves at the sink using a washcloth (the so-called sink wash, bird bath or sponge bath).

The weekly water and energy use of a daily shower quickly surpasses the water and energy use of a once, twice or even thrice weekly bath

The shower is often presented as a more sustainable option than the bath, because the latter is said to use more water. However, the weekly water and energy use of a daily shower quickly surpasses the water and energy use of a once, twice or even thrice weekly bath. The sponge bath is even more water and energy efficient: roughly two litres of water is sufficient to get clean, and the water could even be cold because not the whole body gets wet at the same time.

Taking a sponge bath. Summer Morning, a painting by Carl Larsson, 1908

Environmental organisations, water companies, and municipalities encourage people in industrial societies to take shorter showers, use low flow shower heads, and install energy efficient water boilers. There’s also factors influencing energy and/or water use that these institutions don’t dare to question: shower frequency, water temperature (“take cold showers”), or the act of showering itself – it is never suggested that a sponge bath would actually suffice. Clearly, the daily hot shower is today regarded not as a luxury but as a basic necessity.

Why Do We Shower?

However, showering does not only wash the body. A shower that’s entirely focused on cleaning the body – a so-called Navy shower or Sea shower– takes very little time, energy and water. A Navy shower consists of a 30 seconds shower to get wet, soaping the body while the water is off, and is completed by another 30 second shower to rinse the soapy water.

Until the 1970s, showers were only used in barracks or prisons to wash many people in a short time. Image: La douche au Régiment, a painting by Eugène Chaperon, 1887.

Assuming an average water flow, a (hot) Navy shower uses only 8.3 litres of water and 0.2 kilowatt-hour of energy. A daily sponge bath would have even lower water and energy use. A nine minute hot shower per day is by no means a basic necessity: it’s a treat. Since the 1990s, the daily shower has been portrayed in advertisements as a means of relaxation, stress relief, and sensual pleasure.

Mist Showers

The use of the shower to treat oneself seems to be incompatible with a drastic reduction of its water and energy use. However, there is a technology that might just do that: the mist shower. A mist shower atomizes water to very fine drops (less than 10 microns), which greatly reduces the water flow. Buckminster Fuller invented the first one in 1936 as part of his Dymaxion bathroom (he called it a “fog gun”). The idea was taken up again in the 1970s, when several trials and experiments were conducted with both atomised hand washing and showering.

Left: Mist shower developed by NASA. Right: Mist shower developed by the Canadian Minimum Housing Group. Both are from the 1970s.

NASA developed a mist shower with a hand-held, movable nozzle that incorporated an on-off thumb controlled water valve attached to a flexible hose. The average water use for a nine-minute shower was measured to be 2.2 litres, which corresponds to a water flow of only 0.24 litres per minute. The Canadian Minimum Housing Group developed and tested several mist showers and obtained a flow rate of 0.33 liters of water per minute. . In both cases, swab tests of bacteria on the skin showed that mist showers clean the body just as well as a “normal” shower of the same duration – using 30 to 40 times less water.

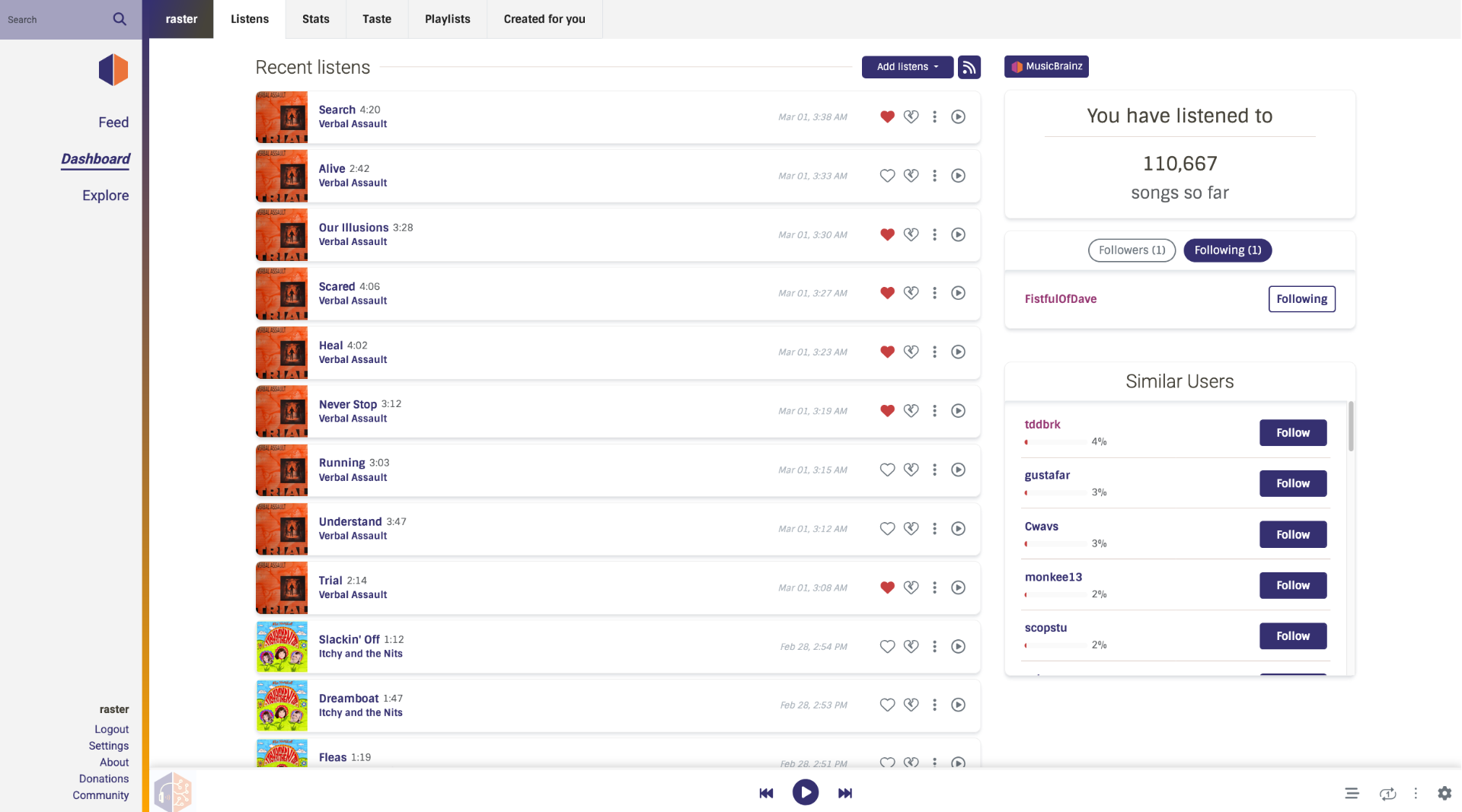

Jonas Görgen developed a kit that converts almost any shower into a mist shower.

Jonas Görgen, a young designer who graduated from the Design Academy Eindhoven in 2019, became fascinated by the history of the mist shower and decided to build one himself. Compared to earlier mist showers, Görgen has improved the concept in two important ways. First, he developed a kit that can turn almost any shower into a mist shower with very little effort. Second, in contrast to earlier experiments, his mist shower uses not one but three to six nozzles. This turns a functional but very basic mist shower (using only one nozzle), into a pleasant experience that feels just as comfortable and invigorating as a “normal” shower.

A 6-nozzle mist shower in the bathroom of designer Jonas Görgen. Image: Jonas Görgen.

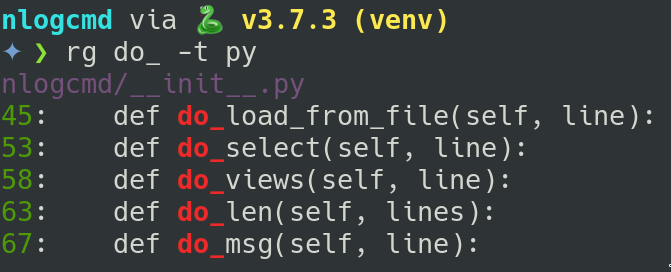

The kit that Jonas sent me contains six nozzles, some connectors and dividers, some flexible plastic tubes (“feel free to cut to any length”), and some pieces of copper wire (“to fix and attach the nozzles in the right positions”). I installed a five-nozzle mist shower in less than twenty minutes, and although the result won’t win a design award (in fact, Jonas built a more beautiful mist shower for his graduation project), as a do-it-yourself shower hack it is simply brilliant.

With five nozzles, I measured a water flow of two liters per minute, which is five times less than my now obsolete shower head

In my set-up, four of the nozzles are fixed (one aimed at the head, one aimed at the back, and two aimed at the hips), while one is flexible and can be aimed where it’s needed — as in the NASA experiments. Using more than one nozzle increases the water flow, but the water savings remain significant.

Image: Detail of a mist shower.

For five nozzles, I measured a water flow of two litres per minute, which is five times less than my now obsolete shower head (ten litres per minute) and 12.5 less than the water flow of a rain shower. It’s unusual to obtain such large savings with so little effort. Jonas writes about his shower that “it is not all a compromise in comfort, as it is sometimes suggested in the research papers of the 1970s” and I totally agree. The difference is clearly due to the fact that earlier mist showers only used one nozzle.

Energy Savings of a Mist Shower

The energy savings of a mist shower are smaller than its water savings. That’s because a mist shower requires a higher water temperature. The increased surface area of the water decreases water use but also causes the heat to dissolve more quickly in the air. Even if the water coming from the tap is at maximum temperature (usually 60 degrees Celsius and already slightly too hot to touch), when sprayed by a nozzle it quickly loses its temperature the further you place your body from the opening. The trick is to position the nozzles in such a way that they closely surround the body. I did this with the iron wires and some duct tape, but there are more elegant ways.

The energy savings of a mist shower are smaller than its water savings

I found a water temperature of about 50 degrees Celsius to be sufficient for thermal comfort, but a mist shower in winter may require a higher water temperature, so let’s assume a value of 60 degrees to calculate the energy use of my 5-nozzle mist shower. At a flow rate of two litres per minute, a 8.9 minute shower consumes 17.8 litres of water. Heating that volume of water from 18 degrees to 60 degrees requires 1.04 kWh. That’s half the energy use of the average shower in the Netherlands (2.1 kWh), and six times lower than the energy use of a rain shower (6.3 kWh).

Details of Jonas Görgen’s do-it-yourself mist shower.

The energy use of a mist shower could be further reduced by showering in an enclosed cabin, which increases thermal comfort with lower water temperatures. Another trick to increase thermal comfort in winter is to open the nozzles a bit so that the surface area of the water decreases. This increases water use but decreases heat loss. It is down to the individual to find balance between saving energy or water, based on local circumstances.

An argument that is often made against water saving shower heads is that people compensate lower water flows by taking longer showers. A similar argument could be made against mist showers, because the use of mist increases the time needed to rinse the body of soapy water. However, a mist shower of 8.9 minutes offers plenty of time to get rid of soap and shampoo. The test subjects in the NASA experiments all managed to wash and rinse within 9 minutes, using only one nozzle on a flexible hose. Washing long hair is more problematic, but also in this case the problem can be addressed by opening the nozzles a bit more, increasing the water flow.

How Many Nozzles Can We Afford?

The five-nozzle mist shower offers significant water and energy savings compared to a “normal” shower and does so without sacrificing comfort. However, is it sustainable enough? If eight billion people used a five-nozzle mist shower, all wind turbines in the world could still only provide two billion people with a daily hot shower. And, compared to a one-minute Navy shower – which is entirely focused on efficiency, not on comfort – energy use is five times higher, and water use is twice as high. So, let’s see what happens when we decrease the number of nozzles, still assuming average shower frequency and duration.

Three nozzles – with a flow rate of roughly one liter of water per minute – are the minimum for providing the comfort of a hot shower

I found three nozzles – with a flow rate of roughly one liter of water per minute – to be the minimum for providing the comfort of a hot shower. This would bring the water use of a 8.9 minute mist shower down to 8.9 litres, which corresponds with the water use of a one-minute Navy Shower. The energy use would come down to 0.52 kWh, two to three times higher than that of a Navy shower. This would provide four billion people with a wind-powered daily hot shower, meaning that if we halved the shower duration (from 8.9 to 4.5 minutes) or showered less frequently (once every two days), the global population could be cleaned and pampered using only wind power.

A nozzle in my mist shower.

If we give up on comfort and simply get clean with as little energy and water as possible, we could take a mist shower using only one nozzle, just like in the seventies. Using just one nozzle I measured the water flow to be 0.3 litres per minute, meaning that a 8.9 minute mist shower would need only 2.67 litres of water and 0.156 kilowatt-hour of energy. The resource use of a mist shower then corresponds to that of a sponge bath, and is significantly lower than that of a one-minute Navy Shower. All wind turbines in the world could provide roughly 15 billion people with a daily 8.9 minute hot mist shower.

If more than fifteen nozzles are used, the energy use of a mist shower is higher than that of a conventional shower

Conversely, the water and – especially – energy use of a mist shower increases quickly as more nozzles are added. With twenty nozzles, the water use is still below that of the average shower (6-7 litres vs. 8.3 litres per minute), but the energy use is already higher: 3.1 kWh compared to 2.1 kWh. With ten nozzles — see for instance the commercially available Nebia Spa Shower — water use remains very low at only 3 liters per minute, but energy use is only 25% lower in comparison to a normal shower (1.45 vs. 2.1 kWh). Mist showers are not low energy products by definition. It depends how we use them.

Off-Pipe

There’s one problem with mist showers operating with only one to three nozzles: modern water boilers don’t get triggered by a flow rate below 1 litre of water per minute, meaning that only cold mist comes out. This is not a fundamental problem – it’s technically possible to make water boilers that heat small amounts of water – and it brings us to another potential advantage of the mist shower: its effect on the bathroom.

I got so fond of my mist shower that I’m travelling with it.

The modern shower is not a device that stands on its own. It is plugged into several infrastructure networks, like the water supply, the sewer network, and the power grid or gas infrastructure. In contrast, although a mist shower could be plugged into the same infrastructures, it could also operate without them, further reducing the use of resources.

Modern water boilers don’t get triggered by a flow rate below 1 liter of water per minute, meaning that only cold mist comes out

First of all, a switch to mist showers would make it possible to use much smaller and less powerful water boilers, which could be powered by local solar or wind powered systems that are smaller and cheaper than those required for conventional water boilers. With a minimal mist shower, one could even question the need for a water boiler at all. The quantity of water is so small (2.67 litres) that it could be heated on the fire – just like in the old days.

A portable mist shower from the 1970s, pressurized with a bicycle pump.

Secondly, because of its high water use, a conventional shower needs to be connected to the drain. The mist shower discharges much less water, which makes it possible to take the shower off-pipe and treat the water on site, for example to flush the toilet, water the plants, or clean the pavement. Third, a water supply in the bathroom is not strictly necessary either: a small container could be filled elsewhere and taken to the bathroom.

The Canadian experiments in the 1970s resulted in such a portable mist shower. The water was stored in a Volkswagen window washing reservoir connected to a bicycle pump to pressurize the water. The 2.5 litres of water were pressurized with about twenty strokes of the bicycle pump. In short, if we switch to mist, the infrastructure that made the modern shower possible can be scaled down and simplified, to such an extent that the bathroom could be taken off-grid and off-pipe even in an urban context, bringing further reductions in the use of water and energy. The same approach could be applied to hand washing and dish washing.

Jonas Görgen‘s mist shower is not for sale yet, but you can let him know if you’re interested. A mist shower is on display at the Dutch Design Week Eindhoven, 19-27 Oct. 2019.

Please note that all showers carry a legionella risk. The smaller water droplets from a mist shower remain in the air for a longer time, which increases the risk of inhalation. Therefore, it is important to take elementary precautions.

Kris De Decker

To make a comment, please send an e-mail to solar (at) lowtechmagazine (dot) com.